In 2020 and 2021, the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) partied like it was pre-Covid 2019. The agency kept running trains and buses at the same levels as in 2019 even though ridership numbers had taken a huge 60 percent plunge due to the pandemic. Passenger fare revenue collapsed, and yet CTA officials didn’t cut operating expenses a penny thanks to billions in federal Covid handouts. Now with the party set to end – federal relief runs dry in 2025 – Regional Transit Authority (RTA) officials say they want tax hikes to keep running Chicagoland’s too-empty trains and buses, including those of the CTA. RTA menu options include higher sales taxes, an increase in the motor fuel tax and even a vehicle mileage tax.

Instead of resorting to more tax hikes on Illinoisans to prop up a failing transit system, the CTA should do something it has never done: make the agency more efficient. CTA must dramatically reduce costs and, given new post-Covid dynamics, cut service to better match revenues.

That said, the best remedy for CTA is a growing, vibrant, and safe Chicago which solves escalating crime, lowers taxes, and fights corruption to attract more of the employers, workers, and convention traffic for which the city was once famous. Since that’s not likely to come anytime soon, the only focus for the CTA should be right-sizing.

RTA sees ridership, revenue drought through decade’s end: it may extend further

Even with the pandemic largely behind us, CTA ridership in 2022 still remains nearly 40 percent below levels in 2019. RTA officials – who coordinate the CTA, suburban Metra commuter trains to and from Chicago, and the suburban PACE bus system – say there will be no full ridership recovery post-Covid. They say that more taxes will have to increasingly replace falling farebox revenues. They identify as causes increased violent crime, the rise of remote and hybrid work, and ride-share services like Uber and Lyft. It’s spelled out in a new RTA report.

“Transit has survived the pandemic, but ridership – and with it, revenue from fares – sustained precipitous declines and has not returned to pre-COVID levels. Related economic shifts and other factors have resulted in a system more vulnerable to violent crime and labor shortages have impacted every aspect of service….(Regional) ridership crossed a million daily rides threshold in the fall of 2022. However, this return is not enough for fiscal stability and puts into question the reliance on fares moving forward. Moreover, ridership isn’t expected to recover to 2019 levels for the foreseeable future. The public health and safety restrictions in place during the pandemic, the increase in people working from home, and changes in how people travel have all combined to drastically reduce transit ridership since March 2020. While riders are returning to the system, the impacts of the pandemic and permanent changes in remote and hybrid work are projected to result in lower levels of ridership for the remainder of the decade compared to 2019.”

Call it a fiscal train wreck enabled by Washington, D.C. Cushioned with a hefty share of $3.5 billion in federal Covid-era transit handouts to Chicagoland transit agencies via the RTA, the CTA ran a pre-Covid schedule with Covid ridership, wasting taxpayer dollars as service frequency far outpaced passenger miles. It was and is unsustainable. Even in October 2022, unlinked passenger trips – meaning all boardings of transit vehicles – were down 38 percent versus the 2019 full-year average.

CTA data reveals a transit agency in fiscal free-fall

As the new push for transit taxes begins to gain steam, here’s a sobering close-up of a transit agency in fiscal free-fall. It comes from CTA reports to the National Transit Database. They reveal much that mere ridership data – the usual staple of media reports – does not. Here are some key data points.

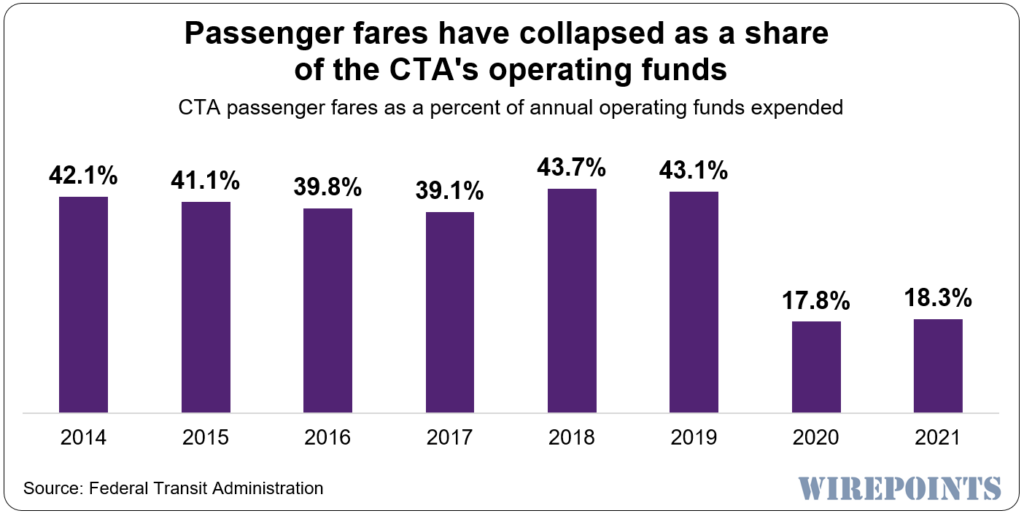

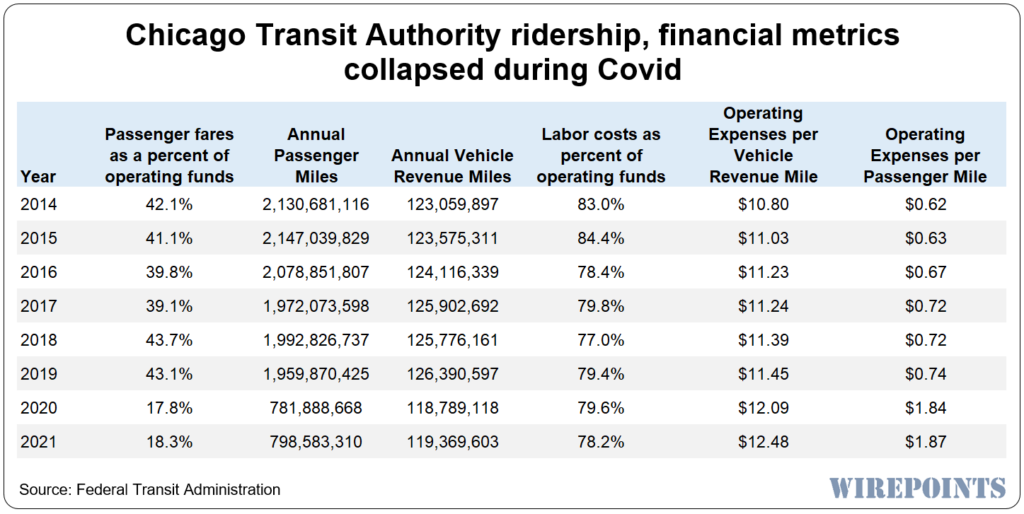

- From 2014 through 2021 CTA farebox revenues as a percent of operating costs plunged from 42 percent to 18 percent.

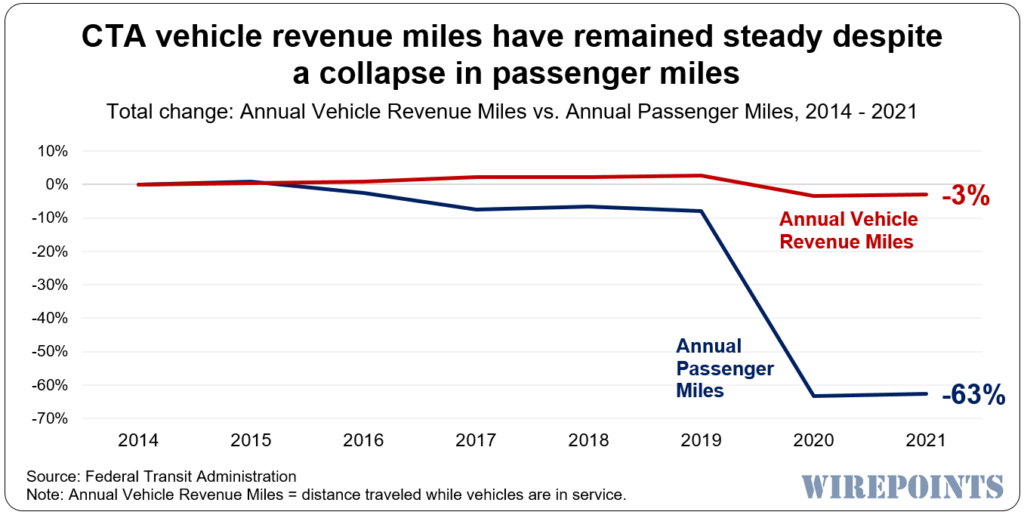

- Annual Passenger Miles for the CTA in 2021 plummeted 63 percent versus 2014 but the number of miles that fare-seeking buses and trains ran – so called “Vehicle Revenue Miles” – was down only 3 percent. In other words, ridership remains sharply down after Covid but service mileage hasn’t budged. On-time performance is far worse, though. More on that in a later section.

- With buses and trains running as many miles as before Covid but drawing so many fewer passengers, CTA’s operating expenses per passenger mile are up 150 percent from 2019 through 2021.

CTA’s steady high costs, diminished revenues, and regional pressure for transit tax hikes are intertwined with three more problems. They are CTA violent crime, CTA service deterioration, and the shift to remote office work.

The City of Chicago’s crime data portal shows that based on results through November 29, year-end violent crime on the CTA will reach a post-Covid high.

Due in some large part to their concerns about on-board crime – CTA is hemorrhaging bus and train operators. This has resulted in highly irregular service or so-called “ghost buses” and “ghost trains” which are very late or don’t show at all.

On top of that, overall downtown crime in the area’s two key police districts show heightened danger for passengers who make it there safely on the CTA and exit to the streets. Despite its many attractions, downtown is increasingly seen as risky territory. That hurts ridership, too.

Murder, shootings, sexual assaults, vehicle thefts rising in and around downtown

In District 1, covering the South Loop and Near South Side through Week 49 of this year versus the same span in 2019, murders are up 533 percent (from 3 to 19). Shooting incidents are up 240 percent. Motor vehicle thefts have risen 324 percent, criminal sexual assaults 20 percent, robberies 21 percent, and aggravated batteries 10 percent. In District 18 covering the North Loop and Near North Side, for year-to-date 2022 versus 2019, murders are up 225 percent (from 4 to 13). Motor vehicle thefts are 141 percent higher, shootings up 83 percent, and criminal sexual assaults have grown by 50 percent.

Meanwhile downtown post-Covid Chicago continues to pose ongoing risks not only for transit users but also commercial lessors and office workers. A number of LaSalle Street office buildings that were long home to financial firms have now emptied out and are being eyed for conversion to apartments. Hefty taxpayer subsidies will be required.

But the trend away from downtown is broader than just financial sector tenants on LaSalle Street. Growing remote work has partially hollowed out downtown Chicago. One metric used by business analysts is mobile phone “locations” or tracked presences within specific areas. In May 2022, these visits to downtown Chicago captured through tracked cell phone location data were only 43 percent of what they were in May 2019, according to a UC Berkeley report.

Key card swipe rates in downtown office buildings have also dropped markedly, though now they have rebounded somewhat. Still, at November’s end, swipes in downtown Chicago office buildings were registered for just 48.5 percent of cards issued, according to Kastle Systems “Back To Work Barometer.” Hybrid work takes a toll. Downtown Chicago merchants in places like the Metra station say they know all too well: Mondays and Fridays, it’s a ghost town.

The takeaway: crime on the CTA and crime downtown threaten to permanently gut CTA ridership if post-Covid work patterns alone do not.

RTA claims that “fiscal cliff” and “existential crisis” require higher transit taxes

The new RTA report acknowledges getting $3.5 billion in federal Covid relief and warns that “this federal relief funding is likely to run out in 2025.” What happens after that? The RTA report rolls out a number of new tax strategies lawmakers will surely consider. They include congestion pricing, a vehicle mileage tax, higher tolls, and increases in the state motor fuel tax and the RTA sales tax.

The RTA tax hike menu also includes expanding the agency’s own sales tax from goods to now-exempt services, and expanding Chicago’s real estate transfer tax from the city to the much larger RTA district.

RTA writes, “…sales taxes and federal emergency funds will keep the region’s buses and trains running into 2025, when our system encounters a fiscal cliff. If the current funding model that is reliant upon fares is not changed and additional funding is not secured, the transit agencies will face an existential crisis that neither fare hikes or service cuts can solve while preserving a useful and equitable transit system for the region.”

Somebody should remind the RTA of the tax burden Chicagoland residents already face. Chicago’s combined 10.25 percent sales tax is already the 2nd-highest of any big city in the nation. Illinoisans as a whole already pay the nation’s 2nd-highest gas taxes thanks to Governor Pritzker’s doubling of the motor fuel tax in 2019. And, of course, Illinoisans already pay the highest effective property tax rate in the country.

The RTA won’t be alone in the line to squeeze more out of taxpayers. Other local and regional taxing bodies will have their hands out too. Layering on more taxes will only encourage wealth and employer flight. It’s a strategy for decay, nothing more.

The right way forward

Of course, the other option is rightsizing service. In the CTA’s case, bad misalignment of current operating expenses with operating revenues should be grounds for a fresh take on service cutback plans after 2023 or 2024 based on several different ridership scenarios.

Chicago’s broader solution, however, should be a focus on growth. If crime, lousy public schools, high taxes, and corruption all deter employers from staying, growing, or moving to Chicago – and that is too often true today – then the way Chicago does business needs to be turned on its head.

Appendix

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up